Valeria and the Ants

Chapter 1

When Valeria was seven years old she liked to play with the ants in the yard in front of the trailer she lived in. I will describe the trailer, and then I will have something to say about the ants.

The trailer had wheels, and could be moved, but it had remained in one place since she was four, and so Valeria did not have any idea yet of the transient nature of things. The trailer was red and black and had a circular window in the door. Tall weeds obscured the wheels but the grass in the yard was trimmed and consisted of patches of grass and dirt.

Valeria was puzzled by the behavior of the ants. She put down a piece of white paper and with a stick she encouraged the ants to run across it, but the ants were apprehensive, and ran away in all directions.

Sometimes an ant would walk timidly across the paper and then, for no reason whatsoever, the ant would back up a little and then go right back where it came from.

She attempted to keep the ants from running off her paper. She tried blocking their way by putting down several twigs in a square around them, possibly it was a trapezoid, I’m not sure.

Valeria noticed that when an ant got trapped in the jail of trapezoid twigs, they became frightened, and when they were frightened they would just sit there, entirely still, without moving, as if lost in thought.

Whenever an ant decided that they were trapped in the twigs, Valeria, after a while would begin to feel bad for them. She would remove one twig, and then another, but still, sometimes they would just sit there, apparently afraid to run away, not being able to know all the implications and considerations of their situation.

Valeria was not in the second grade, which is the place you might find a seven year old. She had not been in first grade either, and you can put out of your mind that she was home schooled. She came from a long line of completely unschooled persons, a line of relatives going back to before the stone age.

I feel it is very important to mention that Valeria was neither in school, nor home schooled because I might have inadvertently given you the impression that she might have known the difference between a square and a trapezoid. If her twig houses for the ants took on some geometric shape, it was entirely coincidental.

So, when Valeria made houses of twigs for her ant family, she could have used three twigs, which would have been a triangle. She could make nothing at all with two twigs, but preferred four twigs in a square, simply for aesthetic reasons, and not because she knew what a square was. Having made a house with four twigs you can guess that after a while she would hit on the idea of a house shape with four twigs in a box, and two more forming a roof. But Valeria lived in a trailer you will remember.

There are some scholars of Valeria’s life that have suggested that her use of the schematic diagram for the house of the ants indicates that she was jealous of the so-called normal children, normal children being those who live in houses that have a triangle on top. I think that idea is obviously wrong.

First of all, you can’t represent a trailer having curved ends with twigs. Everybody knows that if you try to make curves with twigs they break. Even disregarding the obvious technical difficulties of drawing things with twigs, you have to consider that Valeria, even before she was born, was in a category entirely different from so-called normal children, normal families, and conventional society.

Oh, I admit that there might have been times when Valeria, riding her tricycle around the nearby village, might have seen children getting on the bus to go to school, and she might have felt a tremor and wondered what life was like for them, and as the bus pulled away from the curb, didn’t she consider some other seven year old’s face looking at her dreamily out of the bus window, and wonder what the school might be like.

Just because Valeria was not in school does not mean that she was not educated in her own way. She had some remarkable skills, one of which was a memory like flypaper and burdocks, especially for things overheard in conversation. The odd thing about this skill was that although she could remember what she heard, she often had no idea what the words actually meant.

Many highly perceptive children can remember things they hear, but Valeria’s skill had this oddity, she could also accurately imitate the accent in which the words were spoken. Also, she could remember the various facial expressions of the speaker. It was exactly like for a few moments when she was performing one of her “imitations,” she became the person down to fine details.

Certainly there are those who dismissed that skill of hers as the obvious result of being raised in the middle of a carnival troupe, in which she was the youngest member when she was seven. Regardless of how it came about, that skill of her’s was talked about, and one visitor who heard her performance even wrote an article about her which was published in an important journal somewhere.

But how is one to explain the several various unrelated languages she could speak. She was not exactly fluent in other languages, it was just that she could say various unexpected things in foreign tongues, and the things she said always had the necessary accents. However, someone pointed out that usually she did not exactly know what the words meant, and so it was just dismissed as an example of her, “skill of remembrance,” seeing as a carnival entertains people from various places, and she was often exposed to a stranger’s conversation.

Valeria thought it completely natural, and even logical that she should be able to have conversations with the ants in the front yard of her trailer. To this end she began to give the ants various names. She gave them obvious simple names like Tom, and Jack but she found right away that they simply did not know, or were unable to remember what they were called, and this defect on their part made it seem to her that conversations with them would be next to impossible.

Furthermore, she was actually confused to realize that she was unable to tell them apart. This is how she reasoned about not being to tell them apart, she thought, “If I go into the circus tent and I see a great crowd of people, no matter how many there are in the tent, each one will seem to be entirely different, in every way, from any other person in the tent. Now, suppose the ants have a big meeting and they all come together in a group to decide about something important to ants. Don’t you think Valeria,” (She liked to address herself with her name when she was thinking to herself.)

“Don’t you think Valeria,” she continued, “that the ants would know each other apart, and without any difficulty. Obviously they would all be naked, but even so, clothes only conceal a person’s identity.” She was correct obviously, that the ants would know each other apart, but try as she might she could not perceive any differences.

She did manage to make friends with one of the ants who recommended himself to Valeria because he walked with a limp. He seemed to list to one side as he walked and because of this trait he made himself known to her. His limp was the result of having lost a small part of one of his legs in a mishap.

She gave the ant with the short leg the name Syracuse; why she named him that I confess I don’t know and will not offer any theories. The ant Syracuse soon knew his name and would come out of the ground to visit with Valeria when summoned. Syracuse frustrated Valeria because he did not seem to be very intelligent, and knew very few words.

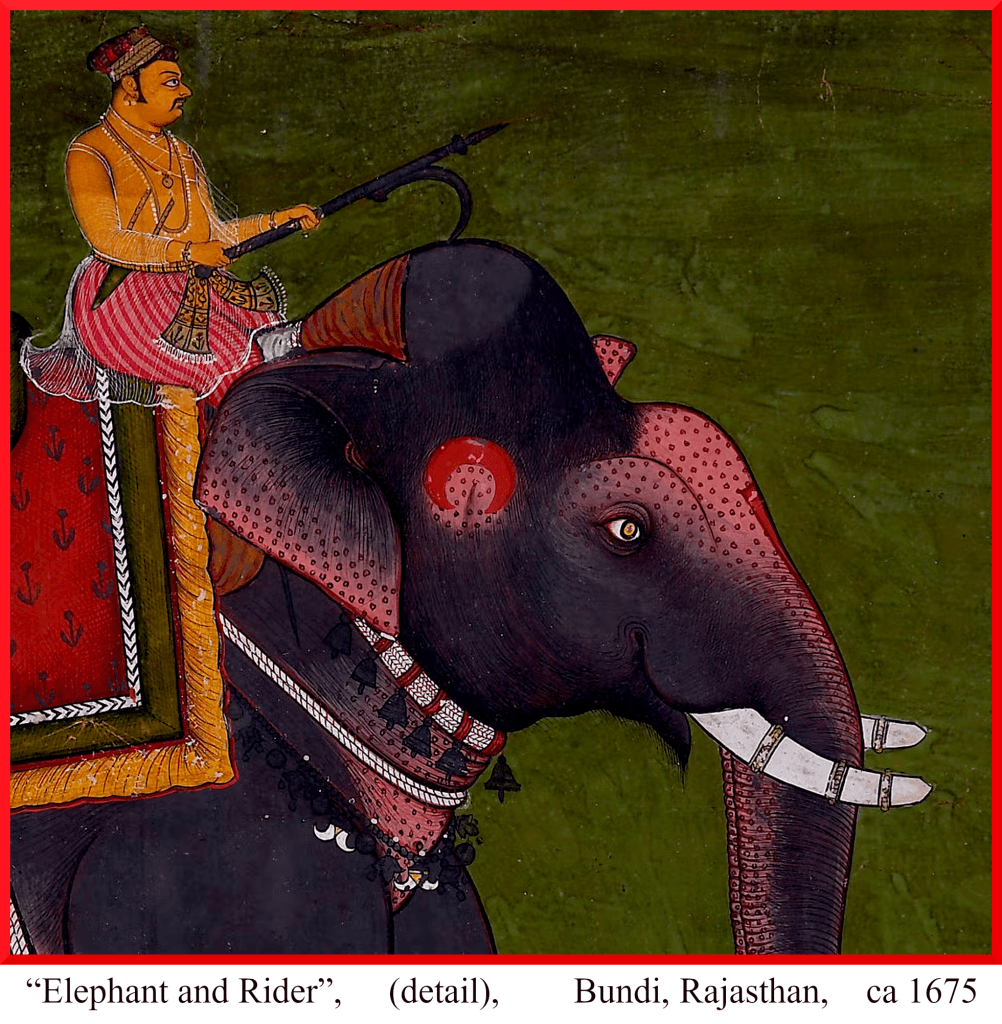

When Valeria became frustrated with trying to conduct a conversation with Syracuse the Ant, she went to have a chat with Bruno, the carnival elephant. I will have to say some things about Bruno, and I am aware that some of my notions about him are very much disputed.

My ideas about Bruno are so much looked down upon in scientific circles that I am really apprehensive to talk about him at all, aware as I am that I might subject myself to ridicule.

But, really, even though my ideas about him are entirely circumstantial, and apocryphal hearsay, nevertheless I know of no other way to explain the relationship between the huge brute, and the child.

If one had the patience to just sit and watch them for a few hours, as I did, I feel certain you would come to the very same conclusions I have come to.

It was as if they were so much of one single mind that they were somehow directly connected to each other, even though she was but a seven year old, and he was fifty, at the least. You could see clearly that they were often engaged in some kind of complicated conversation simply by the wonderful coordination of their head movements, replete with those little noodling motions, and laughter.

So it was obvious, to me at least, that the Elephant was engaged in the education of Valeria, but it was not some intentional course of study, or any kind of programmatic series of lectures or exercises. You could see that Bruno was simply talking to the child, perhaps relating his various experiences.

And to a little child it doesn’t matter if they understand even just a hundredth part of what they hear, because the child’s mind will seize upon the one thing it can comprehend, and hold it in the consciousness like a single puzzle piece, and then wait patiently for the next piece to fit it to, and so over time patiently establishes their picture of the world.

The innocent conversation with Bruno the elephant and Valeria about the ants led to an unexpected disaster, which I will have the tragic duty to describe for you in the next chapter.

Richard Britell, May, 2025

Chapter 2

The Rage of the Elephant

It was obvious that Valeria had learned all of the various bits and pieces of foreign languages she knew somehow, directly from the elephant, by what must have been a form of telepathy. It is the simplest and most obvious explanation of her abilities. He became her instructor not long after she was born.

The elephant was always tethered to a convenient telephone pole, or street lamp, and a circle was drawn in the dirt underneath. The child, when just a few weeks old, was put down on the ground in the circle, and left there for many long hours. The elephant, in his slow and languid way, kept track of all the child’s movements. You might imagine that he would frequently need to shepard the child back into the circle, but that was not the case. Valeria was content to stay put.

But how could I ever describe their conversations, I can’t even begin to tell you what they were like. Take for example, one day the two of them were sitting there next to the lamp post and a man came down the road riding a bicycle. He was a very thin old man with ragged uncombed hair, and he was riding a squeaking bike of dubious reliability. Connected to the back of the seat of the bicycle was a pipe attached to a homemade cart of wood of the type that is made from packing crates. In the cart was a collection of personal items like chairs, bags of clothing, various suitcases, and assorted small furniture items.

As the old man on the bicycle with his load went by, the elephant looked at Valeria significantly, and Valeria looked at him and not a word passed between them.

I could sum up that look with these words, “He is certainly funny to look at but it would be wrong to laugh at him, seeing as he must be desperate and very miserable.”

Perhaps you have been fortunate in your life if you have had a friend such that you could look at each other and know that you are both thinking the same thought, at the same moment, even from across the room, even from the opposite ends of the earth; to have one mind.

So Valeria sat down in her favorite spot next to the elephant, sitting on a three legged stool, with her elbows on her knees, and began to explain her experience with the ants.

Bruno at first listened to everything Valeria said about the ants, but he started to be restive and agitated when she began to recount her conversations with Syracuse, the ant with the short leg.

Bruno became so agitated, for no apparent reason, that he could not stand still, and finally he made a loud bellowing sound, and Valeria heard him say, in no uncertain terms, that if he was going to be friends with some ant named Syracuse, that he could not be friends with himself.

I can imagine what Valeria looked like at that moment. Her face was most likely a perfect mixture of terror and anguish.

At first Valeria could not even believe her ears and she became entirely terrified. She took several steps clumsily backward with her small hands outstretched and than she ran all the way home, holding her hands over her ears like mufflers in the winter, as the elephant continued to bellow, and even tore out the lamp post he was chained to, and began running around in a dangerous way, dragging the lamp post by his chain, and causing a lot of damage.

It took Valeria several hours, actually, more than a day to truly realize what had happened, and finally, on the evening of the day after the event she said to herself, “This is the most terrible thing that has ever happened to me in my entire life.”

First of all, I have to apologize for a very serious mistake in the previous paragraphs. In it, I stated that after Bruno yelled at Valeria about the ants, he tore out the lamppost he was chained to, and went rampaging about destroying things. That statement is categorically false.

Well, actually it is a true statement, even though it is false, but let me explain, because it is very important. Bruno did go on a rampage after he yelled at Valeria, but the rampage happened four days after his altercation with the child. The importance of this distinction can’t in any way be overstated, because if you accept the chronology that placed the elephant’s fit immediately after the argument, then it would appear that Bruno was a distinct danger to the child, and that is a terrible misconception.

Here is what actually happened. Instantly after he yelled at Valeria, Bruno watched as she ran off. She was not covering her ears, “like earmuffs in the winter,” but she was very confused and upset. Bruno was anxious to clear up what he felt was some sort of a misunderstanding, but after several days he realized that he might not get an opportunity.

I happened to be away at the time of the altercation between the elephant and the child, and so my account of the story was based entirely on newspaper accounts of Bruno’s rampage. What I said, I must apologize for, but it was just my amateurish attempt at being “literary.”

But imagine my surprise when, on further inquiry among the carnival folk, I was informed that there was no elephant rampage.

Carnival folk do not read newspapers, and most of them are actually illiterate, and so they had no knowledge of any account of any rampage. The reporter who wrote the story simply made up the details about the lampost knocking over an ice cream stand and the ticket booth, because it made an interesting story.

Bruno did, however, happen to tip over the lamppost he was chained to and this happened because he was in the habit of scratching his forehead on the lamppost, and over time, scratching his head on one side, and then another side, the post became loose and simply fell over of its own accord.

That then, is the entire account of the rage of the Elephant at the carnival, a story that goes right the the heart of the ambiguous relationship between the elephant and humans, and also illustrates the profound advantage the illiterate have over people who read news accounts, when it comes to understanding the truth of simple happenings.

Although there was no rampage, and even though nothing was knocked down, nevertheless, Valeria’s life was completely altered. In the first few days after the elephant yelled at her she went around in a daze, and found it very difficult to think even the most ordinary thoughts.

You can see this state of mind in those people who have experienced sudden catastrophic events. For example, I can remember very clearly the behavior of my old Aunt Mary, when her husband Dominic died suddenly after a brick fell on him at a construction site. And he was not even working at the site, he was just making a delivery of pizza from his pizza shop. The delivery boy was sick that day, and so Dominic was doing the deliveries himself. He was in a tremendous rush, so as to get back to the shop before items in the oven got burned.

The next day, after Dominic’s death, Aunt Mary was eating soup. She was holding the spoon of soup approximately four inches from her lips. As I looked at her I thought, “She is just waiting for the soup to cool off.” But no, she was just sitting there, the soup suspended in the air. I imagine it was her desire to stop time itself, and if it could be stopped, then perhaps she might be able to unwind the spool of time itself, to a better time just simply 37 hours previously.

That was how it was for Valeria, and she thought to herself, “If it could only be just three days ago, instead of right now.”

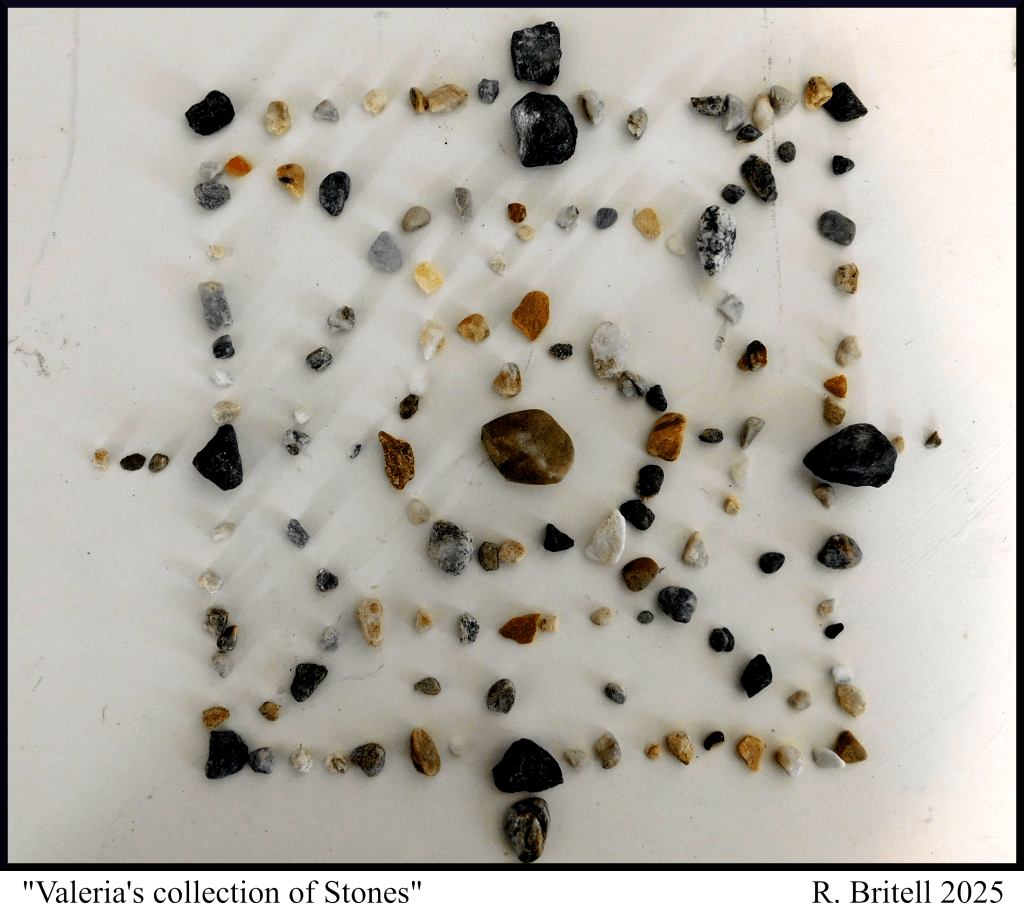

Without the elephant to talk to she went about her daily activities, but in a disinterested and abstracted way. She got out her cigar box that contains about one hundred similar stones and set to work to make a pattern with them. The pattern was a circle in a square, and at each corner of the square, where it touched the circle, she made a kind of little swag shape, and the ends of the swags almost touched each other making a decorative frame for the pattern, but she didn’t finish it because the shapes gave her no satisfaction.

Then she hung upside down from a low hanging branch of the maple tree behind her trailer, but she did not find the upside down view of the world even slightly interesting.

Then she went to have a look in the carnival tent, to see if anything had been left behind by the weekend visitors. She had a small collection of found objects, all extremely valuable in their own way, because of the meaning she attached to each of them, especially a cloisonne thimble with which she could change the weather, depending on which finger she put it on, or so she thought.

Her search was not in vain that day, what she found was a marble, one of those that are perfectly clear, and have no color. She had a collection of marbles in a leather bag, tied with a red string, but in her collection there was no, “purees,” as those marbles are called. She seized the marble in her left hand and went running across the field in the direction of the Elephant. She was excited to show it to him, and see what interesting things he would say about it. Then she stopped suddenly, as she realized she was not on speaking terms with the Elephant.

Valeria dropped the marble, which suddenly had no interest for her. and she said, almost out loud, “I will never be sadder than I am at this very moment, and I think I will never ever be happy again for the rest of my life.”

I ask you, whatever could have possessed the Elephant to yell at the child like that, what could possibly be a cause or a justification. We will delve into it in the next chapter, not to justify the Elephant’s behavior but perhaps to at least understand him.

Chapter 3

The Square Root Of Two

The Elephant was Valeria’s best friend. She had a great many acquaintances certainly, living in the middle of a carnival troupe, but she was only truly close to the Elephant. When she found that she was, “Not on speaking terms,” with him, she did what anyone might do, she sought out the friendship of someone else to confide in.

As you probably know yourself, this never works out in any satisfactory manner. The backup friend never seems to really understand the situation, and often simply feels used and imposed upon. In Valeria’s situation she decided to talk to, and confide in the Ant Syracuse

How would I know the details of Valeria’s conversations with the Ant Syracuse? Simply because at the time of the events related here, I was also one of Valeria’s acquaintances, and so it happened, to my great good fortune, that she confided in me also at the time.

I happened to be working at the carnival, just for the summer at first. I had been planning to go to college, but unfortunately I was rejected by all three of the colleges I applied to. Actually, I was rejected by two of them, and I was on a waiting list at the third school. Being put on a waiting list was somehow even more irritating than an outright rejection. I had applied to only the very best schools, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale were my choices. Harvard and Yale rejected me, but I was on the waiting list for Princeton.

In September, after the semester began I received a very nice letter from them. I had finally received a rejection from Princeton as well, but several freshmen died in a car accident, and so there were several unexpected openings that September, but I sent them a rejection letter! I rejected their damned college, and nothing would have induced me to go there, not even with a scholarship, which they did not offer to me.

When my high school counselor heard that I had been put on the waiting list to go to Princeton he called me down to his office. His name was Mr. Bridges, and I hated him. He had terrible habits. If you went into his office he would invariably be reading something, and without looking at you he would gesture for you to take a seat, with a dismissive wave of his hand. Then what seemed like hours would go by, and finally he would look up over his glasses and say something insulting to you.

“Whatever possessed you to apply to Yale and Harvard. You like to waste people’s time? There was no possibility, with your grades, and your history, that those schools would ever read all the way through your application. You have always been in the bottom third of your class.”

“I’m on the waiting list at Princeton” I said to him in anger, spit unexpectedly flying out of my mouth as I said it.

“That is why I called you down here, to talk to you about it. That has to obviously be some mistake, and I think you should not get your hopes up about it, it is probably some sort of a mistake, some filling error. There is most likely a person with a similar name and the letter was probably sent to you in error. I have a call in to them right now, because I want to clear up the matter as soon as possible. I just don’t want you going around telling people about this, I am trying to help you, and spare you a terrible embarrassment.”

Then his phone rang. It was one of those happy situations where fate inserts itself into your affairs, and contradicts the outline someone has already written for you. It was an administrator at Princeton, calling Mr Bridges to tell him that I was, indeed, on their waiting list. Mr. Bridges said absolutely nothing during the phone call but it was obvious from the consternation, on his face, that he was talking to the school about myself.

But just consider this, Mr. Bridges was my counselor, his job was to encourage me, to be happy with my accomplishments, but No, my success was somehow a slap in the face to him. Why, he should have been beaming with pleasure, he should have jumped up from his chair, come round the desk and given me a pat on the back. In actual fact, he was unable to conceal his disappointment in my accomplishment.

To tell the truth, however, I myself also thought it was a mistake, some obvious mistake. I had received the notification in the mail the day before, and I went right to the phone and called them up. I discovered that I was indeed on a waiting list, and they were specific about it. I was 49th on a list of 51 names.

Then transpired in my life a strange moment of epiphany. Some respected strangers somewhere thought that I was worth something. It was a perfect moment, and yet, I couldn’t really believe it. Like my counselor, I felt that it had to be some sort of a mistake.

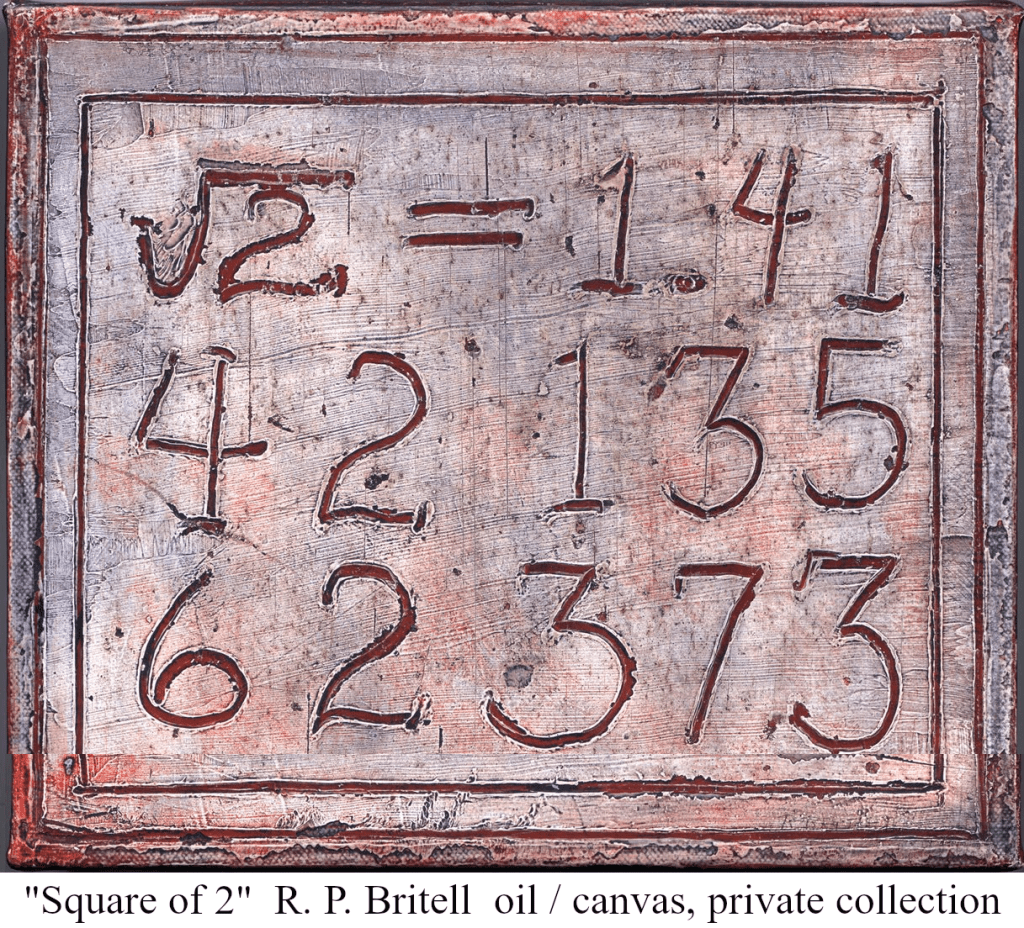

There was only one strange and remote possibility of an explanation, it might have been because of a recommendation written by my algebra teacher, Mr. Jory, with whom I had a peculiar relationship. It began one day when he was explaining irrational numbers to us, like pi and the square root of two. I sat there in class and listened to what for me constituted a monstrous travesty. How could there be “irrational,” numbers? If there was one thing in this world that was completely rational it would have to be the world of numbers. I was so aggravated by the idea that I raised my hand and when Mr. Jory asked me what I wanted I had nothing to say, I was unable to formulate any argument about the problem that the square root of two presented.

After class I approached him timidly and tried to voice my objection to the idea of irrational numbers. He was very pleased by my questions saying, “Young man, you come from a long line of thoughtful people who object to the square root of two. Many famous mathematicians began their careers because of their objection to the concept. “Now,” he said, “let me show you the proof that the square of two must go on forever.” With that he took up the chalk from the chalk tray, and began writing a series of numbers and symbols on the chalkboard, stopping now and then to look at me with a significant expression of pleasure on his face, like as if he was playing the violin.

Finally he finished his “proof,” and turned to me with satisfaction saying, “Now do you see!”

Yes, I see.” I said, but I was lying, I had no idea at all what his proof meant but I was just too embarrassed to let him see how stupid I was.

But there was a more important connection I had with that man having to do with a profound personal struggle he lived with. Mr. Jory was “shell shocked.” I do not know what the proper term is for the condition, but everybody said he was afflicted in that way. He was always jumpy and nervous and one time the wind blew the door shut, and for a moment we thought he was going to pass out. Another time one of those huge window shades rolled up suddenly with that machine gun sort of rattling sound, and the poor man turned perfectly white.

It was said that students in his classes would sometimes, when his back was turned to the class, that it sometimes happened that a student would lift the lid of a desk and then slam it down in order to persecute the poor man. I did not believe that anyone had actually done this, but then, one day a student sitting next to me did it twice. Mr. Jory’s reaction was not anything extreme, but he stopped what he was doing and bowed his head a little, and his piece of chalk made a cracking sound, but then continued with what he was doing. A few seconds after he had recovered himself the desk banged again, and then he started to turn around, thought better of it, and finished his work on the chalkboard. As I remember, it was the Pythagorean Theorem.

When the bell rang there was the usual scraping of chairs and the gathering of books and we all stood up to go. The desk banger next to me had a very large quantity of books and papers that day, and he was hugging them all in both arms when Mr. Jory walked up to him and took hold of him by the shoulders. Then Mr. Jory began to shake the desk banger violently back and forth, left and right and then back and forth again, for good measure. All his books and papers flew about the room, and still the shaking continued. On Mr. Jory’s face was a look of such pure rage that I suppose it was the kind of look one might see on some person’s face, just immediately before a homicide.

Finally Jory stopped what he was doing, perhaps aware of how extremely out of the acceptable order of things he had gotten, and looking around his eyes met mine, and he could clearly see how overjoyed I was to witness what he was doing. Yes, I was happy with Jory that day, he could have been fired, but he was doing the just, right, and only thing that had to be done. Perhaps it was just my imagination, but from then on he began to refer to me by my name instead of “Young Man.”

So, I went to Mr. Jory, and I asked him what he wrote about me in his letter of reference, and he said, “I said you were one of the best of the students I had to fail, and that you hated the square root of two. And to not forget that Einstein failed his way out of high school also.

But in the end, I didn’t go to Princeton, or any other college. But do you imagine, even for a single second, that going to a college could ever be compared to working, even for just a summer, at a Carnival?

Richard Britell, July, 2025

Chapter 4

Death of a Spider

I decided to apply for the job at the carnival on the spur of the moment, it was going to be something to do for the summer, after I was rejected from all of the colleges I had applied to. “Well, Yale didn’t want me, and neither did Harvard, so I will be one of those people running rides at a fairground then.” I thought of it as a gesture of contempt for fate. If not the carnival, well then, I will be a bum.

I went out to the fairgrounds and asked for the manager. The manager was fixing a tractor motor, and seemed to be at his wits end with frustration over it and had no time for me. Not only did he have not a minute to spare to talk to me about some job, he acted like I was somehow responsible for his difficulties with the tractor motor.

I mentioned to him the notice in the paper and it seemed he did not even know about it, as if someone had placed the ad as a prank. Finally he stopped what he was doing, put down an enormous screwdriver on the fender of the tractor, then after having moved the screwdriver just slightly so that it would line up parallel with the edge of the tractor fender, he said.

“Joe died, he ran the bumper cars? You can have his trailer to live in and meals, and fifty dollars a month. Go talk to the assistant manager, she will fill you in on the details. The assistant is Valeria, you will find her in that black and red trailer over there.”

So I went to the black and red trailer and knocked on the door. A child probably 9 years old opened the door and looked at me with curiosity. “I want to talk to Valeria,” I said. “I’m Valeria,” she replied.

Valeria, who was eight “just going on nine,” turned out to be the assistant manager of the fair grounds and the carnival. She was not actually the manager of anything at all, but I was about to enter a world in which nothing was ever taken seriously and everything was deliberately the opposite of what you think it should be. Valeria offered to show me around the carnival grounds, and I told her that I was going to take the place of Joe, who had been in charge of the bumper cars. We began walking together toward the bumper cars ride. Valeria seemed to be lost in thought and then she said.

“Bumper cars!,” and then after a long pause she said, “Do you believe in free will?”

“Why would you ask me about free will young lady?” I said.

“Because free will is the most important aspect of bumper cars. All the other rides in the fairgrounds, and especially the ferris wheel, are the exact opposite of the exercise of free will. Even the scrambler, it seems to go in all kinds of directions unexpectedly, but the passengers have no control at all. But with the bumper cars…”

I interrupted her lecture to say, “Does the lion in his cage in the zoo exercise free will when he decides to pace back and forth rather than taking a nap?”

I didn’t want to enter into a philosophical argument with the child, but even though she seemed to be very serious about what she was saying, I thought that she was putting me on, really actually making fun of me and my future job.

“Will you buy me some fried dough?” she asked. We were just then walking past the fried dough stand.

I purchased two fried dough but the man tending the stand just waved me off when I offered to pay. Valeria took her fried dough and began putting powdered sugar on it with a sugar shaker. She put three shakes on each side as if she had a specific routine for the eating of fried dough, and like she had done it many times before. I felt I was entering someone else’s established world, with rituals I knew nothing about.

Valeria sat down at a red painted picnic table but she did not start eating the dough, but instead set to work picking flakes of red paint from the surface of the table. “Who put the idea of bumper cars and free will into your head?” I asked her.

“That’s really a very insulting thing you have just said to me, don’t you think,” she replied, looking up from her paint chipping project and giving me an angry look.

I instantly felt embarrassed at my thoughtlessness. When I asked her who put the idea in her head, it never crossed my mind that a child would take offence, but I suppose the assumption was sort of belittling and dismissive. She began to eat her fried dough, looking at me angrily as she did so, and I was thinking of some kind of apology, but on the other hand, was I really wrong to say what I said. After all, was she born knowing about free will, the idea had to come from someplace. So I said, “So, were you born considering the idea of free will, and it’s your original idea?”

Pointing to her head with her index finger she said, “It’s not my idea, Joe, the bumper car man put the idea into my head,” indicating a spot just above her ear where the idea had apparently been inserted.

Having said that, she took a bite from her fried dough, and then laughed at me for thinking she was actually angry.

I asked her about Joe, the bumper car operator who died thinking that if he was the kind of person who would discuss free will with a child, he must have been an interesting person, but I was wrong. Valeria explained the man to me with these abrupt comments while continuing to eat the fried dough, and talking to me with powdered sugar on her face.

“Joe was stupid,” she said bluntly. “He had only one idea in his entire life and that idea was about free will and the bumper cars. He explained it to people over and over again, whenever there was a long wait to get in the cars. Not only did he explain it all day long, but even using the same words.” Then, assuming Joe’s voice and his facial expressions she did an imitation of him giving his lecture.

“It was sad though, the way he died,” she continued. “If the cars did not fill up he would ride in one himself, and was always very excited to crash into people. His last trip in the cars happened at closing time, and so he was still in the car in the morning. His head was slumped to one side and the car was still going, and bumping into the wall of the ride over and over. There was something weird about it, and even though you could see that he was dead because his face was blue, nobody wanted to shut the electricity off, and go deal with him.”

“How old was he?” I asked but she didn’t bother to answer the question.

Then assuming an angry judgmental tone, she sat up straight, holding the remains of fried dough at some distance from her face as she pronounced, “Joe is much better off dead.”

I admit I was shocked to hear a child speak dismissively of a dead person, especially when it was a person she knew, but I began to suspect that, like with taking offence about the source of her ideas, she was again baiting me to see how I would react.

I thought to myself, “This has to be the result of growing up in the middle of a carnival, where everything is for effect, and nothing is really real,” but I didn’t say anything. When she saw that I was not going to react to her blunt, insensitive remarks about Joe’s death, she decided to elaborate on the theme, which could have been called, “The goodness of death.”

“When there were no customers for the ride he would sit in a chair with his knees far apart, and with a stick he would poke and dig at a hole in the ground. He always dug at the same hole, and with the same stick, for hours on end. He smoked cigarettes one after another and his fingers were dyed yellow from the smoke. One day something happened and he was taken to the hospital, and when he came back he had stopped smoking, but I noticed that he had switched to chewing tobacco.

Sometimes he would cough for a half an hour at a time. He seemed only alive for a few minutes a day, when he was crashing around in the bumper cars, driving himself into the other kids. At those times you could see him smile, showing his single remaining tooth.”

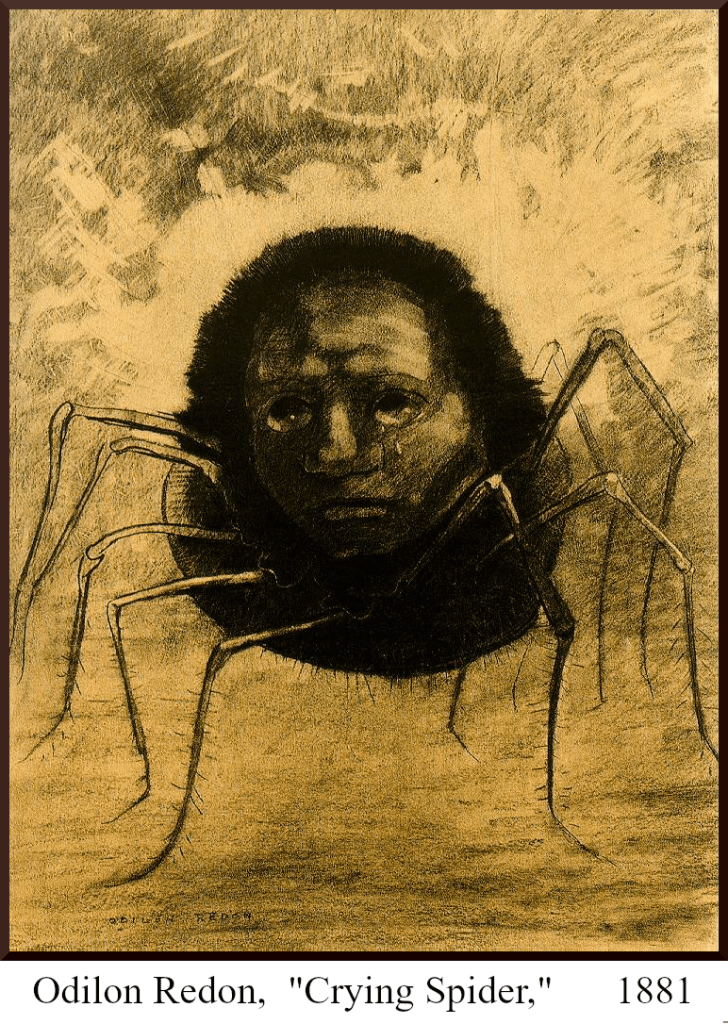

I began to be annoyed by what she was saying and I interrupted her with a defense of life itself, “If you pull all the legs from a spider till they have only one left, the spider with its single remaining leg will try to run away from you.” I said to her almost in anger, and angrily she replied, “How would you know that?”

It was obvious that she knew the answer to her accusatory question but I was unable to confess to the crime and tell her the truth, and I blamed the torture and murder of the spider on my older brother, explaining,

“He thought it would die when he pulled off one of its legs, but then it kept trying to escape until he killed it in desperation.

We were in the old part of the cellar of the house, there were millions of spiders down there, and they were all watching. I am sure they will never forgive us.”

That was how I met Valeria, and our conversation that first day. I started my duties as the attendant of the bumper cars, and the next time I saw Valeria it was just a few days after Bruno the elephant yelled at her. She seemed to be a different person, when she came to see me, and very soon we were talking about the death of insects again.

The Return of the Spider

Chapter 5

Soon after Bruno the Elephant bellowed at Valeria, and told her he would not be her friend if she persisted in her acquaintance with the Ant Syracuse, Valeria went directly to the ant, and told him all about her situation. She explained how her relationship with Bruno was very important to her and she simply could not imagine how talking to an insect could make him so angry.

Syracuse listened to the explanation of her predicament, and, as I have mentioned before the ant did not seem to be very intelligent, and Valeria had noticed that his vocabulary was extremely limited, nevertheless at the word, “elephant,” his entire manor changed completely, and he seemed to be suddenly ‘all ears,’ to hear what Valeria had to say. And so the Ant Syracuse explained the situation of ants and elephants to Valeria, and subsequently she explained it to me, sitting at the picnic table, and eating our fried dough. This is what she had to say.

“Animosity exists between the ants and the elephants, and has existed for a long time, many years in fact. Animosity is really not the correct word, hatred is really more accurate. The ants hate the elephants intensely. They hate human beings also, but not as much.

The ants divide humans into three distinct groups, there are those who will avoid stepping on an ant on the sidewalk. Then there are those people who will not deliberately step on an ant, but will not bother to avoid them either. Then there are those people who will go out of their way to kill the ants. They kill them for no reason whatsoever, and even take pleasure in it.”

“Ants know what people take pleasure in?” I said, interrupting her, but she just shook her head and went on.

“The ants even devote thought to the subject of the patterns on the soles of our shoes, since the tread of a shoe has so often been the difference between an ant’s life and death.

Sometimes, when an ant is stepped on, they come out from the experience entirely unscathed, having found themselves to be entirely within a cavity of the shoe tread. There are others for whom death is instantaneous. What instantaneous death of ants is like, what sort of experience it might entail, they have no idea, although they certainly speculate about it.

Lastly are those ants who find themselves caught in the pattern of the sole in such a way, that part of a limb is cut off.”

At this point in Valeria’s explanation, she stopped just for a moment, and for dramatic effect said, “That is the very thing that happened to Syracuse, he was stepped on by a hiking boot, and lost one half of one of his legs.”

When Valeria said this, I could see that she was very affected by the crippling of Syracuse, and even looked at me with reproach in her eyes, as if I was the sort of person who would step on an ant on purpose, as if I was, in her mind, somehow the actual person who had done the deed myself.

Of course, I was simply listening to what she had to say, and I didn’t have an attitude about it one way or another, but my apparent lack of sympathy for her friend Syracuse was not something she could accept. At first I really did not understand the strange predicament I found myself in, since all along I had been listening to her, but in the back of my mind was the assumption that the ants were imaginary, and just a product of the child’s inventive mind. My reactions to what she was saying might even be compared to one’s reaction to the death of some fictional character you might be reading about in a book. Your tears over some fictional character cannot be compared to the death of an actual friend, even if the friend is a cat. But the dissonance of emotional reaction to a tragedy between two people is a marker pointing to the end of a relationship, and I suddenly felt myself to be on the outs with little Valeria, a situation I very much did not want to have happen.

“Would you pull all the legs from Syracuse, would you watch him try to crawl away with his single stump of a leg…like you did with the spider that time.”

Now I ask you, how was I supposed to react to that comment, and her accusation, which was simply a logical extension of something factual I implied about myself as a child. She was, at that time, still entirely a stranger to me, having only talked to her once before, and so she could not have any idea how the fact that I tortured and murdered a spider when I was just her very age, had troubled and tormented me ever since. She did not know that I had made a vow to myself to never harm an insect ever again, and to even endure without complaint the bite of the mosquitoes, suffering the itch as a reminder of how evil I had been as a child.

But her remarks about Syracuse painted me as one of those children who torture cats in the back yard for the pleasure of it. I felt it was really necessary to defend myself against her accusation, whether she was serious or not. I pointed out to her that her description of the attitude of the ants toward people was lacking one thing. It did not include any mention of those people, suffering from an excess of moral sensitivity, and with outlandish ideas of the judgmental nature of the universe. I asked her, “Did Mr. Syracuse realize that there were those poor souls who, late for work, would spend their time rescuing an ant from the slippery walls of a toilet bowl, and might even shed tears if they failed, or witnessed some spider, who happened to be floating in the water when the stopper in the sink was opened. The spider rushes frantically about, and then disappears forever into the black watery depths.

“And indeed, there are those who, once the spider disappeared down the drain, might continue to torture themselves by picturing in their mind what the spider might be experiencing as they drown in the sink trap. What might it be like to be carried away by the rush of water? Was everything black? Was there any possibility the spider might be able to catch at some bundle of hair on his way down, and then hold on for dear life, waiting out the flood.” Saying all this I became slightly intoxicated with my own eloquence, and began to fear I would start pounding on the picnic table. I felt like I was in court, defending myself from an accusation of murder, and Valeria was the judge and jury. So I continued. “Consider some person who saw the spider disappear down the drain, they’re late for work, and not even completely dressed, standing there at the sink for several minutes hoping against hope that the spider might, by some miracle, reappear at the opening of the sink drain. And then the spider appears, not the entire spider all at once, but first just a single leg, and the single leg is feeling around this way and that, trying to find a foot hold so as to pull the rest of his body out of the fearsome tunnel he was in. He is soaked to the skin, trembling in fear. Think of how that witness to the resurrection and salvation of the spider, some nameless spider might feel. The spider can’t manage to crawl because his feet are wet and the sink is slippery, so that man, understanding the spider’s predicament, rushes to his desk to get a piece of paper to use as a ramp to coax the spider to safety. The paper does not work because the spider is afraid of it and will not approach it, so the man finds a piece of cardboard instead, and he fetches a pencil as well, thinking to put the cardboard to the front of the spider, and then with the pencil, nudge and encourage the little thing to just have a little faith and trust, and accommodate his savior and get up on to the cardboard, and then be transported through the air and out the back door of the house and be placed in some snug safe spot in the grass. Then he can resume his life, catching flies or whatever else he was intending to do.

” But the spider is refusing to be helped, he wants to save himself all on his own, without any help from some person who wants to play the part of an omnipotent being, who has come, as if an answer to his prayers.

But the spider is not willing, and why should he accept help from the half dressed man with the pencil and the cardboard, seeing as he was the very same person who tried to drown him in the first place just moments ago. No, the spider thinks that the pencil and the paper is just another attempt to separate him from his precious existence, and he sets every nerve of his little being, to escape from the pencil point and the paper, dodging first left and then right, drawing himself in, and leaping from one spot to another in desperation, to avoid being saved, at all costs.”

Valeria, listening intently to my story, (a true story I might add, although I presented it as a fiction.) She had stopped eating her fried dough, and, as the story of the spider progressed I could see that I had her complete attention.

I could see from the expression on her face that I had won an argument with her, and although she said nothing, I could see that she was willing, at perhaps some later date, in granting me a pardon.

“So then,” I said, “tell me why do the ants hate the elephants.”

She leaned forward and held up her hands about twelve inches apart, with her elbows on the picnic table and said, “Picture in your mind the elephant’s foot. Now picture in your mind an ant hill,” and saying this, she made a circle with her thumb and her first finger.

Having explained everything with a gesture, she began to elaborate on the feud of the ants and the elephants.

Richard Britell, September 2025

Chapter 6

The Ants and The Punic Wars

It was obvious why the ants hated the elephants, but why would the elephant hate the ants? I was sure Valeria would have some interesting explanation, but some time went by before I had the pleasure of talking to her again. Meanwhile, I worked at my job as the operator of the bumper cars, and I even began to lecture the customers about the free will aspect of the ride, going so far as to make up my own lecture about the superiority of the “free will experience,” as I called it.

I had no stake in the affairs of the carnival or its people, and except for Valeria, I kept my distance from the other members of the troupe. They looked upon me as a temporary hire, and assumed I would soon depart. They even went so far as to talk about me in the third person, when sitting just a few feet away. They referred to me as “Joe’s Replacement,” as if that was my first and last name, and after a few weeks I started to call myself “Free Will Joe,” when people asked me who I was.

One day on my way to my station I saw in the distance that Valeria was talking to the owner himself. They were too far away from me for me to hear their conversation, but I stopped to watch them for a moment. She went on about something, and he listened to her attentively. Their roles seemed to be reversed, like she was a teacher reprimanding a student who was doing poorly in school. Then, she walked away from him and I passed her walking on one of those dirt tracks bicycles make in a field. I said, “What were you talking to the boss about.” “Thats’s none of your business,” she answered, but then perhaps thinking it was too harsh a reply, she said, “Will you buy me a lemonade.”

Just like with the fried dough, the lemonade stand person refused my money when he saw I was with Valeria, and we sat down at a blue picnic table, and like before, she said nothing and started to pick at the blue paint with her fingernail. On her little finger she had a cloisonne thimble.

Although she had refused to tell me about what she was talking to the boss about, I could see that she was troubled about something, so I asked, “How is Syracuse doing?” This was perhaps the wrong question to ask her, because she just shook her head a little and said nothing. “And the Elephant Bruno, how is he?” I asked.

She suddenly became animated and said, almost shouting, “He wants me to kill all the ants. He says for me to exterminate them. I tried to explain that they are nice harmless beings, but he says, ‘Pour kerosene on their ant hill, light it on fire, show me where they are, I will stamp them out.’ but those ants really have a right to hate the elephants, do you know, can you imagine what it is like for them when an elephant steps on their little city.”

Somehow I wanted to prove to her that I was capable of feeling sympathy for the little things so I said, “Well, I guess it would be like if a giant meteorite fell on a city, everyone would die instantly, and all the buildings would be crushed flat. It would be happening so suddenly that they would not even have time for suffering. Everything would stop in an instant.” “And they would not even know why,” she said.

“But the elephants hate the ants because they crawl up into the insides of their trunks and make them sneeze. A few ants can cause an elephant to sneeze over and over again for half an hour.”

“But really, and for this Bruno wants them to be all exterminated, he can’t appreciate it from an ants’ point of view?”

“No, there is more to it than that, it is a historical thing and quite complicated.” Suddenly she was reluctant to go on with her explanation, and I could see that to further elaborate on the subject was going to cause her a painful emotional effort. I said nothing but she had difficulty speaking, looked at me pleadingly, and choked on her words a moment, then pulling herself together she proceeded to give me a most fascinating tragic history lesson. This is what she said.

“Elephants remember things for a long time, and they have a collective memory, what one elephant remembers, they can all remember if they chose to. Not only that but they do not really have any sense of history, and actually, why should they. What an elephant experiences this morning for example, is just the same, more or less, as some similar morning a thousand years ago. If an elephant stubbed his toe a thousand years ago, then they can still feel the pain today, if they want to.”

Having delivered this prologue, Valeria looked at me carefully, she seemed to be trying to figure out if I understood what she just said. I suppose she was thinking, “Why go on explaining if he can’t understand or even believe what I am saying.” But I encouraged her to continue, trying my best to conceal my skepticism.

So she continued, “A long time ago there was a great war someplace. There were two armies and one had elephants and the other army had no elephants. The army without the elephants had a difficult time because their soldiers ran away at the sight of the beasts, which they imagined were indestructible, and possibly even immortal. The elephants in the elephant army were trained in the art of war, and took delight in stamping out their enemies, and squishing them into the ground in the same way that you see people putting out cigarettes. Spears, arrows and sword cuts did absolutely no harm to the monstrous beasts, so that the…

“Romans,” I said, interrupting her. “You are talking about the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage, where the Romans had no elephants. I read about it in my last year of high school.”

Valeria seemed to be quite disappointed that I knew about the war and so, for an instant seemed unwilling to continue, and with a certain sad tone she said, “So then you know all about how the ants caused the Romans to win the war then?”

“No, nobody ever said anything about ants, there were no ants involved in the Punic wars.”

“SO, you are telling me that the best, most important, and most interesting thing about the war was left out?” she said. “Well then, I certainly see that school is meaningless,” and then, with a certain animation she began again excitedly. “The ants had, for a long time, figured out that it was the elephants that had been destroying their cities, and they saw the war as a perfect opportunity to avenge themselves for the wrongs that had been done to them. And so, by the thousands, during the night, before a big battle, they crawled up into the elephant’s trunks and waited for the trumpet to sound, and for battle to begin. Just as the armies were about to clash, the elephants fell into terrible sneezing fits and…”

At that point I could not suppress a laugh at the absurdity of what she was saying, but with an angry look she said, “What’s so funny?” I apologized immediately and she continued with her fable.

“The army with the elephants was completely defeated, and all the elephants were captured and chained together into the middle of a big field. Now the emperor of the Romans put out an order for none of the beasts to be harmed in any way, thinking that they could be trained to fight for the Romans, but the army hated the elephants to such a degree that all the elephants were put to death starting on the afternoon after the battle.

The killing of the elephants was a thing that Bruno found almost impossible to describe to me, he didn’t want to explain it to me and at first all he said was ‘It took them a week, do you understand what I am telling you, it takes a week to kill one of us. We elephants do not die so easily, we have to be stabbed and clubbed for hours on end, and even then we don’t really, at first, feel anything. But the Romans were very inventive and industrious people, and they devised machinery to hoist us in the air, way above the trees, and then we were dropped on tall pointed stales that’…”

“But he would not go on, he would not go on and it was clear to see that even now he could feel those stakes, and so I did not make him go on.”

Bruno’s statement that it took a week to kill an elephant, affected me deeply. I had been listening to her and trying to conceal my skepticism, and also being careful to suppress any tendency to laugh at the more ridiculous aspects of the story, but toward the end, when she explained how the elephants were dropped onto pointed stakes from a great height, I was suddenly moved to tears, and had to make a strenuous effort to repress my emotion and hide my reaction from the child who was talking to me. I shifted my position on the picnic bench and turned my head to hide my face, as if something had caught my attention somewhere.

When I had recovered my composure I turned to her and said “Well, now perhaps it will be your mission to reconcile things between the elephants and the ants after all these years, and such misunderstandings, perhaps it is your duty in this life to…”

“That is not going to happen,” she replied because the elephant is going to be sold next week, and the boss has already taken a deposit. He is going to be sold into zoo slavery.” “Is that what you were talking to the boss about then?” I asked her

“Yes,” she answered, again twisting the thimble on her little finger absentmindedly. Just then it started to rain, and we got up from the picnic table. She walked away down the bicycle path but after a short distance turned around and asked,” Did you cry about the elephants?

Chapter 7

“The Man who Looked Like James Joyce”

After my conversation with Valeria where she explained why the elephants hated the ants, I was surprised at my unexpected emotional reaction. Bruno’s statement that it took a week to kill an elephant had affected me deeply. Nevertheless, I did not believe any of her stories, it was, to me, simply an interesting historical fiction narrated by a child, but reinforced by the child’s emotional commitment to the importance of the story.

It began to rain persistently at that time and there were no patrons at the carnival. Running the bumper cars for only 2 or 3 people was not allowed so I spent some afternoons in the library. I took down an encyclopedia and began reading about the Punic wars. I recognized all the basic facts from high school but there was a passage about the Island of Sicily that said. The important Greek colony of Syracuse in Sicily at first sided with the Romans against the Carthigians, but after a revolt in the city, they switched their allegiance to Hanibal. The Romans had great difficulty subduing Syracuse, because of the mathematician Archimedes, who had created monstrous grappling hooks that lifted the Roman triremes up in the air to a great height, and dropped them to their complete destruction.

Although the Romans finally conquered Syracuse, orders were given to spare the life of Archimedies, but he was slain by a Roman soldier in the heat of battle.

There were several things in that passage that struck me as extremely interesting and relevant to Valeria’s account of the conflict between the ants and the elephants. First of all, I hope you noticed that the town in question was named “Syracuse,” the very name she had given to her ant friend. To me this was a clue to how the story she told me might have come about, though a patchwork of remembered facts overheard over time and stitched together in her inventive mind.

Consider the fate of Archimedes, it was ordered that he was to be spared but was killed anyway. That is what happened to the elephants, they were also ordered to be spared but killed despite the order. Consider also the method used to kill the elephants; by the use of mechanical devices that raise them in the air and drop them. That was exactly the same as the tools Archmedies created in the war.

But where were these pieces of information coming from? She would obviously explain her source of information as being from the ant and the elephant themselves, and I had no desire to question her, or contradict her, but in the meantime I began to look around for a simpler and more obvious explanation.

There was a man working at the carnival who seemed to me to be a possible source of her notions. He was a man by the name of Thomas, and in the past he had been the driver of the old carnival bus, which he was also the mechanic for. For several years the carnival had been fortunate to be able to stay in one place, so that Thomas had no work to do, but he was kept on, partly because he asked for no payment, and made himself useful whenever things needed to be repaired. I mentioned that those employed in the place were mostly illiterate. But Thomas was a highly educated man. How did I know he was highly educated? Because of his eyeglasses, his hat, and the sportcoat he always wore that was tweed, and had suede patches on the elbows. I suspected he wanted to look like James Joyce, and if that was true, he certainly achieved an accomplished imitation.

He spoke little, and when he did say anything it was devoid of any uncertainty. Each morning he would read a newspaper, sitting at a picnic table, and his coworkers would sometimes approach him, even timidly, and sometimes ask him questions. They asked him questions, not because they wanted or needed to know the answers, but just because they liked to hear his answer. So, the man who operated the merry go-round might come up to him and say. “Thomas, when did the Second World War end?” And he might answer, “September of 45,” without looking up from his newspaper, or looking to see who had asked the question.

“But what day in September?” and Thomas would give the date and day, with a slightly annoyed shake of his head.

Why would the Merry-go-round operator need to know the day the Second World War ended? For no reason, but simply because Thomas knew, and therefore, obviously must know everything, absolutely, and it gives an ignorant person pleasure to know someone like that.

This Thomas person was in the library the day it was raining so hard, and I decided to ask him a question, even though we had never been introduced. I walked up to him, he was sitting reading a newspaper in the periodical section, and I said to him, “Is it true that the carnival is going to sell the elephant.” “He nodded his head, not looking up from his magazine. “Is the elephant really mad at Valeria, like she says he is?”

I suppose it was a presumptuous and impolite question and he didn’t bother to answer it but I persisted and said, “Why would they sell the elephant?”

Thomas gestured for me to sit down, and looking at me with great seriousness said, “It’s the end, the end of everything, and when Bruno goes everything else is going to go with it. The money from the sale of the elephant will be almost sufficient to pay all the outstanding bills, and then we are going to all go our separate ways, and everyone knows it.”

Thomas was then good enough to sit back in his library chair, push his papers aside, and proceeded to explain the affairs of the carnival to me in detail. But before I tell you what he had to say, I have to confess that at first I did not like Thomas, and for a trivial and unimportant reason that I am embarrassed to admit. I did not like him because when I interrupted him he was reading the Wall Street Journal, and not only that, but he was making notes in a notebook as well. Now, there are many people who read financial journals, and many of them jot down notes in a pad, but it is a special class of persons, in my opinion, who do this in a library, reading a paper they did not pay for, in a room provided for them by the city. In short, it is… well I won’t go on exposing my various prejudices for you, and will simply tell you what he had to say about the carnival where we both happened to be working. This is what he had to say.

“It is a very odd situation for a carnival to remain in one place for a number of years. In general, carnivals, like our establishment, move from place to place, traveling at least once a month if not more often, and are constantly on the road. How did it come about that we have remained here for so long? It happened quite by accident. One day we set up our tents, booths and rides in an accommodating field, near a small town, only to discover that, without realizing it, we were within sight of the interstate highway. We discovered that it was possible to see the tops of our tents and their flags, from the highway, and as cars would come to the top of a rise in the road there we would be, beckoning travelers to take a break from their journey and visit us. But, it was not the sight of the tents and banners that was so attractive to them, it was the elephant that happened to be tied to a telephone pole just within sight of the road. Now there is something compelling and hypnotic about an actual live elephant, and I believe that there is no person, no matter how busy, jaded or insensitive who, when they round a curve, and an elephant comes into view, would not instantly put their foot on the brake, and slow down to get a better look at the sight.

An actual elephant, looked at close up in the real world is capable by simply existing, to make one feel that their life has been entirely meaningless. The elephant does not have to do any tricks at all to produce that reaction. If you got to stand next to an elephant, say, just two feet away, it seemed as though the animal is just the kindest entity in the world, kind and patient, and even caring, and yet it could kill you with just a gesture and perhaps not even notice you.

I remember, as a child I went to camp each summer, and in a field I could see two buffalo standing motionless in the distance. They were real live buffalo, looking like they must be the last of their kind in the world. I would be riding in the back seat looking for them the entire way. I would feel a rush of joy when I would see them each year. It was so long ago, and yet, when I think of them now I feel as thought they must still be there.

It is like that with our elephant, and it is not just the elephant standing there by his pole, it is also Valeria, sitting next to him, leaning her back against one of his legs and pretending to read a book to him, and him turning the pages for her. A few years ago you could have seen them playing checkers. They loved to play tic tac toe in the dirt, and recently they have been playing chess together. Now, neither of them is very good at chess, so we have been told by people who know, but the sight was something one could never forget.”

Having listened to Thomas explain things to me concerning the carnival, the elephant, and Valeria, I began to have some attachment for the place, but what he said was not even the half of their problems.

Richard Britell October, 2025

Chapter 8

Tolstoy and Curious George

I asked Thomas about the elephant and the ants, “Is the elephant really mad at the child, and because of the ants no less, like she claims?” He did not answer my question, at least not right away. Then with a sigh he said, “What can I say, she goes every morning and puts the chess board in the grass, she sets up the men and makes the first move, but he ignores her, and turns away. It is really just the saddest thing.”

Previously Thomas had explained to me that it was true that Bruno the Elephant would not interact with the child Valeria, although they had previously been inseparable. The idea that the elephant was angry about some ant that Valeria had befriended was the cause, he thought, was idiotic and not worth even considering. I also disregarded Valeria’s explanation, but the fact remained, Bruno would not play chess with the child, whereas in the past it was a part of their daily interactions.

“Do you see the significance of this development?” Thomas asked me, as we sat talking in the library. “The behavior of the elephant is problematic in many serious ways which at first we had not realized. The first consideration was this: was the elephant sick, and if he was sick in some way, was this sickness a danger to anyone. The article in the newspaper that said, erroneously, that the elephant had gone on a rampage and destroyed things is now being brought up, and given new importance. I know it is true that Bruno had knocked over the lamp post, and the lamp post had damaged one of the stands, and even though it was obvious to all of us how this had happened, still everyone is now anxious to have the elephant taken away as soon as possible, and especially as there was someone willing to purchase the animal.

“And the elephant is not our biggest problem,” he continued, “we now, for the past year, have some serious competition. There is a tourist attraction just ten miles north of us called ‘There Yet.’ It is a resort that features a water slide, in a beautiful location just off the highway, and on a river.

“The water slide is not any competition in the winter, but when summer comes they take away more than half of our visitors. They called it ‘There yet,’ because that is what children in the back seat are always crying out, ’Are we there yet.’ This was very smart of the people who set it up. People stop there, just like they used to stop to visit us, but then when they get back in their cars, they certainly are not going to stop again ten minutes later, regardless of any elephant. And so, with or without Bruno, we are now a thing of the past, and everyone talks about us using only the past tense, and everyone has become nostalgic for the old days when we were on the road all the time.”

“And so” I said, “Why not just go back on the road again?” “That sounds very easy when it is just a matter of some words in a sentence, but to make it happen first we would have to get all the transport trucks and tractors into working order with their old antique engines that have not been started in over four years. And all our employees are used to a sedentary life. Take you for example, do you yourself want to be on the road?

“But we may have to go on the road, after the elephant is disposed of. The amount of money involved may be sufficient to finance the launch of our new life, but how can it succeed under such a cloud. During the past four years a veritable myth, a fable of the magic power of Valeria and the elephant has evolved among our folk here in our little society. Valeria fortunately knows nothing about it, because these idiots at least have the common sense to realize that a child might be corrupted by so much attention.”

“Are you really sure that the folk, as you call them, are really successful in keeping the child from knowing their attitude towards her. The other day I saw her giving a lecture to the boss himself, and it is obvious that he highly values her opinion about things, and I have noticed that the vendors will not charge me for drinks or food when I am talking to her.”

With these comments I attempted to insert my observations, but Thomas ignored me and started talking about the cloisonne thimble she always had on her finger. “So you know what the folk think about her thimble? They think she is capable of controlling the weather. If she wants the sun to shine, she puts it on her index finger, and if she wants it to rain she will put it on her little finger. Now, without saying anything about it to her, I have watched her with that thimble, if it starts to rain she puts it on her little finger, and if the sun comes out she will put it on her index finger, and she does this as a little game, her private childish game she plays by herself. Now our folk have decided that the entire process is reversed, and she makes it rain with the thimble, and makes the sun shine with it.”

I said nothing to him about it at first, but then I said to him, just as a question, “I was talking to her yesterday and at one point she put the thimble on her little finger, and right then it began to rain?”

“So,” he replied, “you too are susceptible to superstition? Really wouldn’t it be wonderful if there was a magic child in the world who could change the weather, talk to elephants, and who knows what else she might be able to do for us. But I am telling you simply, unless she can use her magical abilities to get rid of the water slide amusement park, we are done for, but really, I don’t mind as I am ready to go back on the road again.”

I made the comment about the thimble and the rain intending for it to be comic and curious, and not as a declaration of belief in the supernatural, but Thomas just laughed at me and shook his head but…

There are times, I have found, that people will state the opposite of what they really believe, and when you challenge them they become yet more insistent. I began to suspect that Thomas was not being completely honest with me. He knew Valeria much better than I did, as I had only talked to her twice, but Thomas had been with the carnival for several years and I simply did not think it was possible to be acquainted with the child and not have some suspicion that there was something inexplicable about her. Thomas was both an intelligent and educated man and so I thought that he did not want to say what he really thought about the situation for fear of being thought of as, ‘superstitious,’ and perhaps even worse, as being no different than the folks, as he derisively referred to them.

Now, please believe me when I insist that I myself did not believe Valeria was some magical child, but her strange abilities caused me to question in my heart the very idea of what we call ‘cause and effect.’ Could a child affect the weather with a thimble? The idea was stupid, but at times I found myself somehow believing it, these ideas made me doubt my reason.

But now I knew something about Valeria that, supposedly the child did not know about herself, and so there was the prospect of a degree of awkwardness in the prospect of talking to her again. This is a common problem. Someone in confidence, tells you something personal about a friend, that is supposed to be a secret, and one’s relationship to that person is disrupted, and so you will understand that I resolved to go directly to her and explain that some simple minded people thought she had some magic powers and could do things like change the weather.

As luck would have it, Valeria herself was just then leaving the library with two books in her hands, and so we walked the mile to the carnival grounds together. I asked her what she was reading. “I can’t read yet,” she answered, “But I intend to learn to read using these books, so it doesn’t really matter what books they are, as I have to start somewhere.”

She held both books out to me perhaps for my approval and so I read the titles to her, the books were Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” and the other one was “The Complete Adventures of Curious George.” It was easy to see how she might have been attracted to the Curious George anthology, but I did not think War and Peace was some accident, and handing it back to her I asked, “Did Thomas suggest this book.” “Yes,” she said, “he is going to help me to learn how to read, and he said this is the best book for the beginner.”

“War and Peace,” just the thing for a nine year old to learn on, I thought but this confirmed my suspicion that it was Thomas who was filling the child’s head with war stories of the ancient past.

But those two books were really a subtle portrait of Valeria at that special time in her life because she was as sophisticated and intelligent, like some college sophomore, and at the very same time just a child still playing with dolls, and talking to her dolls in that scolding and affectionate way children lovingly talk to their toys. In talking to her I had to be careful not to offend her childhood sensibilities, and at the same time I had to also manage to keep up with the complexity of her thinking because I could see clearly, and was not ashamed to admit that that at nine years old she was both more intelligent and more observant that I was.

“So, won’t you please tell me all about Thomas,” I said.

Valeria and the Ants

Chapter 9

The Trunk of Coins

As Valeria and I were walking back from the library I asked her about Thomas. She told me that she knew Thomas, “As long as I can remember,” and then she said, “He is the smartest person in the world.”

When we reached the carnival grounds I went first to the fried dough stand and Valeria sat at the picnic table, and so began our third conversation.

The subject of the conversation turned out, really by accident, to be Thomas, who I realized was like a mentor to her, and the most important person in her life after the elephant, if you consider the elephant to be a person.

Her first remark about Thomas was a question, and the question, as it turned out, was a complete description of the man and his life. She asked me, “Do you know that there are people who are very rich, and yet, at the same time they have hardly any money at all?” Then, without waiting for me to answer her question she continued. “His grandfather, who is dead, a long time ago, left him tons of money. But even though he gave him the money it is locked up someplace, in a cave, and he can’t even ever get to it or see it.

“The money is in a cave in a beautiful trunk which is locked up with chains. The money is in silver coins, and the coins have an owl on one side, an owl with big eyes, and on the other side is a woman, probably a goddess.

“The coins in the trunk are magical, because if you take one of them away, after a certain time a new one appears to replace it. There is an old man with a crooked beard who is the only person who knows where the trunk of coins is, and he removes one each month and sends it to Thomas. Thomas has to sign papers to receive the coin, and even though he gets one a month, still the trunk remains full.

“Thomas is not the only person in the world who has a special trunk, but some of the other people insisted on taking ten, and even twenty coins all at once, and then the total taken out was not replaced, but instead, the total shrinks down to nothing, not all at once, but little by little.

“You can’t actually buy anything with the owl coins but if you put one in a box, the next day the box can be found to be full of five and ten dollar bills. The number of five dollar bills is different each month, sometimes more and sometimes less. But the silver owl is nowhere to be found.

“At the end of each year, around Christmas or New Year’s Thomas gets two of the coins as a special gift, and each year, as long as I have known him he gives me one of them.”